Dan Donoghue

Dan Donoghue

This evening I was just lounging around thinking about BGP, as you do, and reminded myself about an interesting quirk in IP.

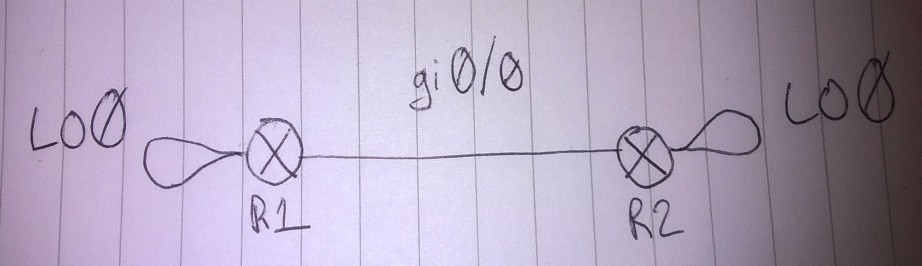

The way I was taught BGP at University emphasised using Loopback interfaces to move the single-point-of-failure you’d get physical interfaces, to a less-error prone virtual interface. In a basic two router lab setup with loopbacks implemented on both routers, this makes the network look something like the diagram below.

So what’s quriky about that? It gets a bit more interesting when you look at the configuration.

router bgp 64496

neighbor 10.0.0.2 remote-as 64497

neighbor 10.0.0.2 ebgp-multihop 2

neighbor 10.0.0.2 update-source Loopback0

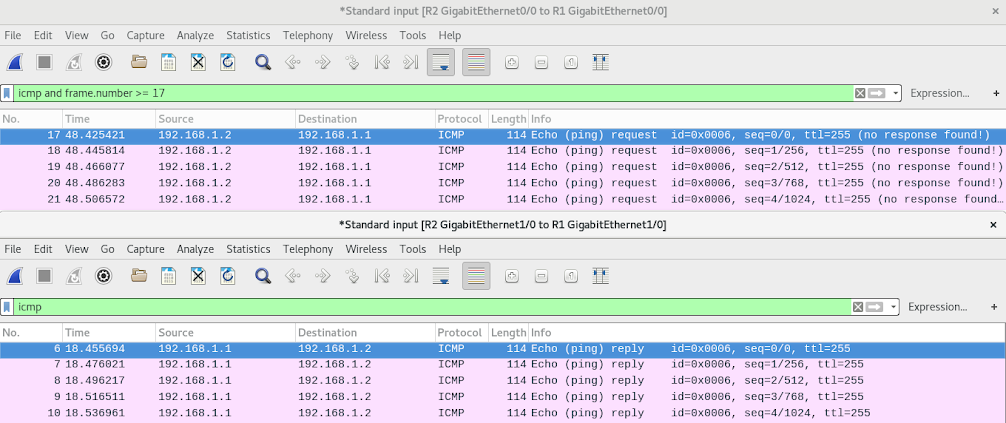

The interesting line is the one that says ebgp-multihop 2. You need to set that for EBPG when the neighbour is more than 1 hop away. This option is set to 2 hops, but in my brilliant diagram there’s clearly three hops between lo0 on R1 and lo0 on R2, and yet this works.

What’s happening is that the routers are accepting and processing the packets at the interface nearest to the source, even if the destination address doesn’t match that interface. This works, as long as the destination address matches any of that nodes interfaces. This is shown in the screenshot above, where an ICMP Echo enters the router via one interface, and the Echo-Reply leaves the router using a different interface, specifically the interface that has an address or route that’s closer to the source address.

If you think about it, this way makes sense from a performance viewpoint because performing that extra hop for the packet to end up at essentially the same place is a bit inefficient.

This behaviour isn’t just limited to routers either, it’s also there on end-node stacks like the one in Linux. It’s supposed to work that way.

There’s no problems with the behaviour, in principle, but in practice things are a little shady. Because packets can come in on one interface, and be replied to from another, this opens up the possibility for someone to perform a blind attack against a node without the victim node even needing a route to the outside. This means that to be absolutely sure that your node can’t receive unsolicited traffic, you have to be sure that none of the other nodes it can connect to have any connection to a lesser-trusted network.

Imagine that I’ve sent an ICMP Echo packet to a node connected to two networks, one public, and one private (no routes to other networks, including public); but I’ve spoofed the source address to that of a node on the private network and sent the packet from a node on the public network. The node I just pinged will send an Echo-Reply out onto the private network, from an event I triggered from outside.

Since anti-spoofing techniques are quite commonly implemented these days, and that blind attacks are one of the most difficult methods of doing any serious damage; knowing this information is kind of irrelevant, but interesting nonetheless.